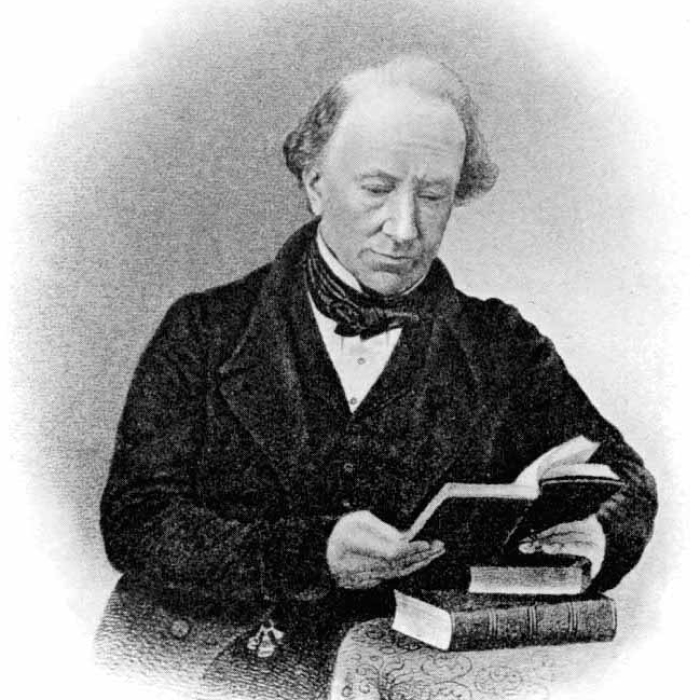

James Cowles Prichard

James Cowles Prichard was a British physician specializing in what would now be considered psychiatry—he is the inventor of the term “senile dementia”—but whose historical reputation derives primarily from his work in physical anthropology, a discipline of which he has often been called the founder. Without ever having attended school, Prichard entered the University of Edinburgh, publishing a doctoral dissertation at the age of twenty-two with the title of De generis humani varietate (On the origins of human varieties, 1808). Five years later this text was greatly revised, expanded, lavishly illustrated, and issued with the title of Researches into the Physical History of Man and dedicated to “the venerable and universally celebrated Professor Blumenbach.” Thirteen years later, Prichard undertook another massive revision, and did so again for a third edition, both of which bore the title of Researches into the Physical History of Mankind. A fourth edition that consisted, like the third, of five volumes appeared in 1841-47. The entirety has long been regarded as one of the most significant works of physical anthropology published in the first half of the nineteenth century, and the most influential and detailed pre-Darwinian account of human variation. It is in Prichard’s work that race appears, perhaps for the first time, not as a complex fact to be described but as a scientific problem awaiting solution.

Prichard was a committed monogenist, an ardent abolitionist, and an early member of the Aborigines’ Protection Society, which had been founded by Quakers in 1837 as a largely philanthropic organization arguing for the interests of indigenous populations affected by British colonialism. The Ethnological Society of London was founded by Prichard and others in 1843—following the creation of the Société Ethnologique de Paris by William-Frédéric Edwards in 1839—as a more purely scientific organization devoted to what was then the fringe science of “ethnology” (on Edwards, see Michelet). Prichard was thus at the center of a remarkable nexus, closely engaged with several of the most urgent political and intellectual issues of his day.

Prichard’s scientific thinking was informed, and constrained, by the Biblical premise that humankind originated with a single pair, a conviction that led him to the conclusion that all currently observable human differences were present from the very beginning of the species. In sharp contrast to his contemporary William Lawrence’s rejection of evidence drawn from the Bible, Prichard did not seek to disprove “the truth of the Mosaic records,” as he put it in the preface to the first edition. At the same time, he had no patience with dexterous readings of Genesis such as that of Isaac de la Peyrère’s Prae-Adamitae (1655) that allowed for the existence of other groups not mentioned in the main narrative, as if the Bible concerned only a single group and not mankind as a whole.

Prichard was a key transitional figure in several respects. While citing Virey, Bory de St.-Vincent [see Cuvier], Linnaeus, Camper, Soemmering, White, Buffon and others, Prichard went well beyond all of them in making race an object of science. His approach was holistic and proceeded from the conviction that all aspects of people needed to be examined, not simply their skeletal measurements, hair, and skin color. An accomplished linguist cognizant of the work done by Sir William Jones, he raised the issue of the pertinence of historical linguistics to ethnology. He came closer than all his contemporaries, with the exception of his fellow monogenist Lawrence, to explaining human variation as the consequence of evolutionary processes, arguing that the differences among human beings were attributable to a process of “natural deviation” that began with chance appearance of genetic “sports” or anomalies that were then perpetuated in subsequent generations. And he was among the first to propose an “Out of Africa” theory of human origins, saying, in the first edition of his work, that “on the whole there are many reasons which lead us to the conclusion that the primitive stock of men were probably Negroes, and I know of no argument to be set on the other side”*—a boldly provocative argument, with an implication that Adam was black, that was, however, removed from subsequent editions.

Prichard was entirely dependent for his evidence on the observations of others, but his innovations consisted largely of a series of rejections of previous theories, beginning with the foundation of the race concept itself, a belief in immutable differences among human groups. Prichard’s use of the term race is quite loose: sometimes it seems to be equivalent to species while at other times it is used along with varieties, nations, or “tribes of men” (Turks, Greeks, Hottentots). On occasion, Prichard resists the term race, suggesting in the passage from Book II, below, “Considerations Relative to the Question,” that the “late introduction” of the term has misled people into confusing varieties with species. Prichard’s own preference was for “permanent variety,” a term slotted between species on the one hand and type, kind, or variation on the other that he used to refer to new creations produced by inundations or other catastrophes. He rejected in particular the idea of a “Caucasian” or “white” race.

Prichard’s second rejection concerned the traditional theory of the “chain of being” espoused by Long, Jenyns, Kames, White, Cuvier and others. This metaphor, as Prichard saw it, carried the implication that the fabric of creation contained no gaps or voids—which, in turn, implied that some groups must be intermediate between full humans and primates, a space invariably occupied, in such theories, by African Negroes. (In the first edition, Prichard quoted but did not endorse the judgment of one traveler who described the “natives of Malicollo” as a group that “of all men I ever saw border the nearest upon the tribe of monkies” [275]).

The third rejection concerned the research done by Camper and Cuvier on skull measurements, which Prichard took seriously but found to be inadequate for drawing conclusions about human groups. The fourth and most consequential rejection concerned the customary support for monogenesis, the view proposed by Montesquieu and others that climate could be the primary determinant for the differences between human varieties. Prichard insisted that culture or mode of living had to be taken into account as well, with domestication or cultivation in particular producing heritable variations. The emphasis on the downstream effects of culture enabled Prichard to argue in the first edition of his work that while the “primitive stock” was Negro, the processes of civilization had carried some human groups away from both barbarism and blackness, resulting in a lighter complexion in the advanced cultures.

Over time, Prichard’s thinking itself evolved, with the later editions of his work registering the growing influence of polygenist, innatist, and anti-environmentalist arguments even as he continued to insist on the unity of the human race and its derivation from a single stock. While his first edition had focused on the similarity between major human groups and the likelihood that they had all emerged from a single region, subsequent editions, informed by considerably more detailed knowledge about the peoples of the world, stressed the characteristic differences between groups and the causes and expressions of those differences. As early as the second edition, Prichard replaced the argument for an African origin of humanity by the a more general assertion that the “natural and original complexion of the human species” was “melanocomous,” or black—black-haired, that is, a trait shared by indigenous people in America and Africa, as well as by Hindus, Spaniards, Persians and “black-haired Europeans in general” (220, 221). [On this conclusion, see James McCune Smith.] In the fourth edition, Prichard omitted all discussion of heredity, variation, and race formation.

The focus on differences in the subsequent editions results in a different tone in parts of Prichard’s work. While in the first edition his very extensive ethnographic descriptions of the various populations of the world were descriptive and often appreciative, in later editions, he includes harsh judgments, often derived from French sources, of the primitivism or savagery of indigenous cultures. Often these came in the form of quotations from others, as when, in Book II, Chapter VI, Prichard quotes a Dr. Vrolik, who describes the African female pelvis as a “degradation in type,” or when in the second volume of the fourth edition, he cites “Mr. Lander” as saying that a certain African group was “a harmless stupid race . . . who are treated with contempt by their neighbors and sold into slavery,” along with the confirming judgment of another author who described them as “more stupid-looking than wild.”**

Prichard also included in the later editions judgments of his own on non-white indigenous peoples, who are occasionally described in terms that do not appear in the first edition: “repulsive” is used several times in descriptions of dark-skinned peoples, including the “generally ugly” women of Papua, who seem to Prichard to be “formed for servitude and obedience” (246, 252). “The Australian women, still more ugly than the men, have squalid and disgusting forms,” he notes in the fourth edition; “the distance which separates them from the beau idéal appears immense in the eyes of an European” (257). In general, the later editions of Prichard’s work imply a biologized and naturalized understanding of human variation, signaled by the greater prominence in his discourse of the term race, a greater emphasis on taxonomy, and a diminished emphasis on the effects of geography and climate.

Perhaps the most telling indicator of Prichard’s shifting perspective is his increasing emphasis on physical characteristics, including craniology, in the 1841 fourth edition. Citing William-Frédéric Edwards, Robert Knox and others, and including accounts of his own studies, Prichard treats craniology with considerable respect, and though he ultimately rejects skull measurements as a reliable source of information, he entertains the thought that Negroes have diminished intellectual capacity compared to Europeans, and reports without comment the judgment of a 1785 study on the ratio of the brain to the central nervous system that concluded that “the Negro displays in this respect an approximation to the lower animals.” (In his 1850 The Races of Men, Knox would denounce Prichard’s hesitation to endorse the race concept.). Elsewhere, Prichard notes that the face of the “Mosambique Negroes may be compared to the face of an orang” (299). His detailed account of “The Psychical Characters of the Bushman or Hottentot race” (Book II, Chapter II, Section III) is Dantean in its accelerating sense of disgust and horror.

In these sometimes small but suggestive and potentially significant shifts of tone or emphasis in Prichard’s work, we can see signs of a larger transition from the Enlightenment ethos of progressive social development towards perfection as overseen by philosophy and theology to the hierarchical classification of humankind proceeding under the aegis of race science. And within race science, Prichard’s revisions document a transition from the affirmation of human solidarity established by God and an environmental account of human differences, and toward the notation of measurable differences established by science and confirmed by “the eyes of an European.” Prichard’s progressive qualifications of his original assertions about the unity of the human are subjected to a merciless scrutiny by Josiah C. Nott in Types of Mankind (54-56).

While Prichard himself never fully abandoned his monogenetic and humanitarian commitments—indeed, in 1843 he published The Natural History of Man, in which he affirmed once again his belief in the intellectual and moral unity of humankind—his later work gave occasional voice to the suspicion that race was a category comparable to species. This suspicion would grow stronger in the scientific community in the years following Prichard’s death as fewer scientists felt obliged to find ways to reconcile current information with the received Biblical account of creation. With belief in the literal truth of the Bible on the wane and nothing to replace it yet in evidence, the theory of monogenesis began to lose ground to its polygenetic rival.

The passages printed here are taken from the first volume of the fourth edition of Researches into the Physical History of Mankind, which contains Prichard’s most developed ideas on evolution. The only edition to be edited and published since the nineteenth century is a facsimile reproduction of the first, which includes Prichard’s conclusion, omitted from later editions, that mankind first appeared in Africa.

*James Cowles Prichard, Researches into the Physical History of Mankind (first edition), ed. George W. Stocking, Jr. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1973), 238-39. A similar view was voiced by Arthur Schopenhauer in a supplement to The World as Will and Idea (1819): “ I may here express my opinion in passing that the white colour of the skin is not natural to man, but that by nature he has a black or brown skin, like our forefathers the Hindus; that consequently a white man has never originally sprung from the womb of nature, and that thus there is no such thing as a white race, much as this is talked of, but every white man is a faded or bleached one.” Supplement to the Fourth Book, Chapter XLIV, “The Metaphysics of the Love of the Sexes,” translated R. B. S. Haldane and J. S. Kemp, The World as Will and Idea, vol. 3, 6th edition (London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co., 1909), 358.

**James Cowles Prichard, Researches into the Physical History of Mankind, vol. II, fourth ed. (London: Houston and Stoneman, 1851), 118.

Researches into the Physical History of Mankind

Fourth edition, Vol. 1

Introduction.

Section I.—General Statement of the Inquiries which form the subject of the following Work.

There is scarcely any question relating to the history of organized beings, that is fitted to excite greater interest, than inquiries into the nature of those varieties in complexion, form, and habits, which distinguish from each other the several races of men. . . . [If] a person previously unaware of the existence of such diversities, could suddenly be made a spectator of the various appearances which the tribes of men display in different regions of the earth, it cannot be doubted that he would experience emotions of wonder and surprise. If such a person, for example, after surveying some brilliant ceremony or court pageant in one of the splendid cities of Europe, were suddenly carried into a hamlet in Negroland, at the hour when the sable tribes recreate themselves with dancing and barbarous music, or if he were transported to the saline plains over which bald and tawny Mongolians roam . . .—if he were placed near the solitary dens of the Bushmen, where the lean and hungry savage crouches in silence, like a beast of prey, watching with fixed eyes the birds which enter his pit-fall, or greedily devouring the insects and reptiles which chance may bring within his grasp; —if he were carried into the midst of an Australian forest, where the squalid companions of kangaroos may be seen crawling in procession, in imitation of quadrupeds;—would the spectator of such phenomena imagine the different groups which he had surveyed to be the offspring of one family? (1-2)

Introduction.

Section II.—Probable Considerations on one side of the Question.

That every part of the world had originally its “autochthones,” or indigenous inhabitants, adapted to the physical circumstances of each climate, is the conjecture which any person who allowed himself to speculate upon the subject would be at first inclined to adopt. . . .

This doctrine, in the first place, appears to account for all the varieties in figure and complexion which are observed in different nations. It explains the diversity of colour so remarkable between the native races of Africa and the inhabitants of Europe. It accounts for the woolly appearance of the hair in the Negro tribes, and for its flowing and glossy texture in the Esquimaux, and for the peculiar features and structure of limbs belonging to either race, by representing these nations as tribes of people originally distinct. . . .

The history of languages presents facts which are very difficult of explanation, while we maintain the opinion that all the families of men, and all their dialects are derived from a common origin. . . . How then are we to account for the origin of so many distinct forms of human speech as we know to have existed, on the hypothesis that all the races of men are descended from one family? On the supposition that these races had the commencement of their existence separately, or by distinct originals, all such difficulties vanish.

By adopting the same opinion we may save ourselves the trouble of accounting for the origin of moral and intellectual diversities, or for the differences in manners and habits which have been thought to characterise particular races. As tribes of animals differ from each other in instincts and other physical qualities, so the various human races, if such exist, may have had their peculiar endowments of intellect and their characteristic habits.

. . . It has often been observed that whenever the enterprising spirit of modern navigators has brought them to hitherto unknown lands, though ever so remote and difficult of access, they have almost invariably found such countries already stocked with inhabitants. . . . These considerations have disposed many to adopt the opinion, that each distant country was originally provided by Nature with a peculiar stock of home-born inhabitants. (3-5)

Introduction.

Section III.—Of Arguments which are urged on the opposite side of the Question. Relation of these Inquiries to the Scriptural History of Mankind.

I must now proceed to consider some of the most obvious reasons which have been adduced in support of an opposite opinion.

There is, in the first place, one argument which has been thought by many to be conclusive as to the whole question, and to render any further investigation superfluous. I allude to the testimony of the Sacred Scriptures, which appear to ascribe one origin to the whole human family. . . . I am not prepared to adopt an opinion which has been expressed by writers of various times, that the Scriptures of the Old Testament comprise only the history of one particular family of men, and that other tribes may have been created to whose origin they make no allusion. To me it appears evident that by the writers themselves, who were employed in the composition of these books, the Holy Scriptures were contemplated and set forth as containing a record of the dispensations of the Almighty Creator to all mankind; and if this be the fact, it can hardly be doubted that an account is comprised in them of the origin of the whole human family. (6-7)

Introduction.

Section V.—Method to be followed in the Investigation.

It appears to be the general result of all these considerations, that we cannot obtain satisfactory evidence . . . from historical testimony, or from arguments founded on general probabilities. It only remains for us to seek it through the medium of researches into the natural history of the organized world . . . . In the way of investigation thus suggested, the inquiry resolves itself into the two following problems.

- Whether through the organized world in general it has been the order of Nature to produce one stock or family in each particular species, or to call the same species into existence by several distinct origins, and to diffuse them over the earth generally and independently of propagation from any central point; in other words, whether all organized beings of every particular kind can be referred respectively to a common parentage?

- Whether all the races of men are of one species?—whether, in other words, the physical diversities which distinguish several tribes are such as may have arisen from the variation of one primitive type, or must be considered as permanent and therefore specific characters? (9)

Chapter III. Of the Dispersion of Animals.

Section IX.—General Inferences from Facts relating to the dispersion of Organized Beings—Bearing of the Conclusion obtained on the History of Mankind.

There appears to have resulted from the foregoing inquiry, sufficient evidence to establish one out of the three hypothetical statements which were expressed at the commencement of this investigation, and to show that the other two are irreconcilable with the phenomena of Nature.

- The hypothesis of Linnaeus, that all races of plants and animals originated in one common centre, or in one limited tract, involves difficulties, which in the present state of our knowledge amount to physical impossibilities. It is contradicted by the uniform tenour of facts, both in botany and zoology.

- The second hypothesis, which supposes the same species to have arisen from many different origins, or to have been at the period of their first existence generally diffused over separated countries, is also irreconcilable with facts. It does not appear that Nature has everywhere called organized beings into existence, where the physical conditions requisite for their life and growth were to be found.

- The inference to be collected from the facts at present known, seems to be as follows:—the various tribes or organized beings were originally placed by the Creator in certain regions, to the local conditions of which each tribe is peculiarly adapted. Each species had only one beginning in a single stock; probably a single pair, as Linnaeus had supposed, was first called into being in some particular spot, and the progeny left to disperse themselves to as great a distance from the original centre of their existence, as the locomotive powers bestowed on them, or their capability of bearing changes of climate, and other physical agencies, may have enabled them to wander.

The bearing of this general conclusion on the inquiries hereafter to be pursued is sufficiently obvious. We have now to investigate the question, whether all the races of men are of one species in the zoological sense, or of several distinct species. If it should be found that there is only one human species in existence, the universal analogy of the organized world would lead us to the conclusion, that there is only one human race, or that all mankind are descended from one stock. (96-97)

Chapter I. Analysis of the different Methods of determining on Identity or Diversity of Species, Section I.—Meaning attached to the terms Species—Genera—Varieties—Permanent Varieties—Races.

The meaning attached to the term species in natural history is very definite and intelligible. It includes only the following conditions, namely, separate origin and distinctness of race, evinced by the constant transmission of some characteristic peculiarity of organization. A race of animals or of plants marked by any peculiar character which it has ever constantly displayed, is termed a species; and two races are considered as specifically different if they are distinguished from each other by some characteristic which the one cannot be supposed to have acquired, or the other to have lost through any known operation of physical causes; for we are, hence, led to conclude, that the tribes thus distinguished have not descended from the same original stock. . . .

Varieties, in natural history, are such diversities in individuals and their progeny as are observed to take place within the limits of species. Varieties are modifications produced in races of animals and of plants by the agency of external causes; they are congenital: that deviation from the character of a parent-stock which is occasioned by mixture of breed, has been regarded as a kind of variety . . .

Varieties are distinguished from species by the circumstance that they are not original or primordial, but have arisen, within the limits of a particular stock or race. Permanent varieties are those which having once taken place, continue to be propagated in the breed in perpetuity. . . . The properties of species are two, viz. original difference of characters and the perpetuity of their transmission, of which only the latter can belong to permanent varieties. . . .

The instances are so many in which it is doubtful whether a particular tribe is to be considered as a distinct species, or only as a variety of some other tribe, that it has been found by naturalists convenient to have a designation applicable in either case. Hence the late introduction of the term race in this indefinite sense. Races are properly successions of individuals propagated from any given stock. . . . The real import of the term has often been overlooked, and the word race has been used as if it implied a distinction in the physical character of the whole series of individuals. By writers on anthropology, who adopt this term, it is often tacitly assumed that such distinctions were primordial, and that their successive transmission has been unbroken. If such were the fact, a race so characterised would be a species in the strict meaning of the word, and it ought to be so termed. (105-09)

Chapter II. Analogical Investigation Continued—of the Psychological Comparisons of Human Races.

Section VI.—Concluding Remarks

If the evidence adduced in the foregoing pages is sufficient to establish the conclusions which I have ventured to deduce from it, it may be affirmed that the phenomena of the human mind and the moral and intellectual history of human races afford no proof of diversity of origin in the families of men; that on the contrary, in accordance with an extensive series of analogies above pointed out, we may perhaps affirm, that races so nearly allied and even identified in all the principal traits of their psychical character, as are the several races of mankind, must be considered as belonging to one species.

Nor can it be pretended, that any intellectual superiority of one human race over another, which can be imagined to exist, furnishes any argument against this conclusion. If, for example, it were allowed that the Negroes are as deficient in mental capacity as some persons have asserted them to be, this could not prove them to be a different species, since it must be allowed that there are differences equally great, and even greater, between individuals and families of the same nation. . . . [There] is nothing more probable than the supposition, that the average degree of perfection in the development of the brain as of other parts of the system, differs in different nations with the diversities of climate and other elements of the external condition, and with the degrees of social culture. It is probable that the condition of men in civilized society produces some modification in the intellectual capabilities of the race. (215-16)

Chapter VI.—Varieties of Form—Diversities of Shape in the Skeleton.

Section I.—General Observations—Varieties in the Shape of the Pelvis in different races of Men.

It has long been suspected by physiologists that several national varieties exist in the form of the pelvis, and that there is some correspondence between these diversities and the shape of other parts of the skeleton, and even of the skull. The first writer who devoted much time and research to this inquiry was Dr. Vrolik of Amsterdam . . . .

Vrolik has remarked that the differences between the pelvis of male and female Europeans are very considerable, but by no means so striking and well marked as those which are perceived when we compare the male and female of the Negro race. “The pelvis of the male Negro,” he says, “in the strength and density of its substance, and of the bones which compose it, resembles the pelvis of a wild beast, while on the contrary, the pelvis of the female in the same race combines lightness of substance, and delicacy of form and structure. Yet the pelvis of the female Negro, according to the same writer, though of light and delicate form when compared with that of the male, is in all the examples with which he is acquainted, entirely destitute of that transparent portion in which in the European female pelvis the bony plates are closely united. He has found this transparency in the pelvis only in one old Negro female, in which however the part in question, when held up to the light, yet appeared not entirely destitute of diploë intervening between the bony plates. . . . Delicate, however, as is the form of the pelvis in the female, it is difficult, as Vrolik thinks, to separate from it the idea of degradation in type, and approach towards the form of the lower animals. This character is imparted by the vertical direction of the ossa ilii; the elevation of the ilia at the posterior and upper tuberosities; the greater proximity of the anterior and upper spines; the smaller breadth of the sacrum; the smaller extent of the haunches . . . . All these characters, as he says, recal [sic] to our minds the conformation of the pelvis in the simiae. (323-25)

Chapter VII. Analogical Investigation Continued.

Section II.—Of Peculiarities in the constitution connected with the Varieties of Colour.

. . . Men of the choleric and melancholic temperaments, which are both characterised by black hair, are well known to have generally sounder and more vigorous constitutions, and to be less susceptible of morbific impressions from external causes than the sanguine. The Negro constitution has some peculiar morbid predispositions, but in many respects is endowed with greater vigour than that of lighter complexion. The muscular fibre in the Negro is said to be of a brighter red than in the generality of men, and capable of more vigorous contraction. (345)

Chapter VIII, Analogical Investigation Continued.

Section IV.—Recapitulation and Conclusion of the Analogical Inquiry.

In the first chapter it was attempted to be proved . . . that tribes of animals which belong to different species differ from each other physically in a variety of particulars, in which the most dissimilar of human races betray no such differences . . . . Secondly, different species of animals have different diseases, are subjected to different pathological laws, if I may use such an expression. All human races are liable to the same diseases . . . . Thirdly, distinct species do not freely intermix their breed, and hybrid plants and animals do not propagate their kind beyond at most a very few generations, and no real hybrid races are perpetuated: but mixed breeds, descended from the most distinct races of men are remarkably prolific. The inference is obvious. If the mixed propagation of men does not obey the same laws which universally govern the breeding of hybrids, the mixed breeds of men are not really hybrid, and the original tribes from which they descend must be considered as varieties of the same species. . . . [All human races] have common affections, sympathies, and are subjected to precisely analogous laws of feeling and action, and partake in short of a common psychical nature, and are therefore proved, with the same degree of evidence which has been obtained from the general observation above laid down, to belong to one species or lineage. (375-76)

Hannah Franziska Augstein, James Cowles Prichard's Anthropology: Remaking the Science of Man in Early Nineteenth-Century Britain (Amsterdam: Rodopi, 1999).

Brett Henze, “Scientific Definition in Rhetorical Formations: Race as ‘Permanent Variety’ in James Cowles Prichard’s Ethnology,” Rhetoric Review, 23 (2004) 4: 311-31.

George W. Stocking, Jr., “From Chronology to Ethnology: James Cowles Prichard and British Anthropology 1800–1850,” Introduction to the facsimile edition of the 1813 first edition, Researches into the Physical History of Man (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1973), ix-cx.

George W. Stocking, Jr., Race, Culture, and Evolution: Essays in the History of Anthropology (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1982).