Joseph Deniker, William Z. Ripley

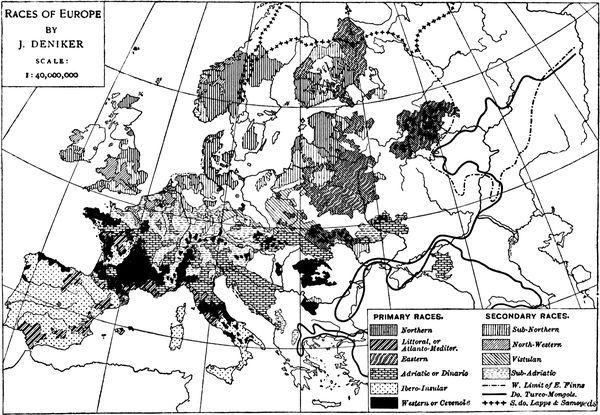

An accomplished linguist who had also published studies in comparative anatomy and the embryology of the anthropoids, the Russian-born Joseph Deniker was, at the time he wrote The Races of Man, librarian of the Musée d’Histoire Naturelle in Paris. He had also served as an editor of the Dictionnaire de géographie universelle, an experience that informed one of his most striking contributions to the theory of race, a radically innovative “racial map” of Europe that was printed in The Races of Man. With one hundred and seventy-six illustrations, including many photographs, this book represented the most exhaustive and well informed account of the racial composition of the human species that had appeared, a remarkable summa of available knowledge of languages, anthropometric measurements, and the geographical distribution of various races.

Prior to Darwin, it had been possible to approach the question of race by several routes, including language (see Jones), tribal affiliations (see Prichard), geography, climate, hair color, bone structure, cranial size and shape, brain, blood, and skin. After Darwin, it became possible and even for some obligatory to consider race as a consequence of the evolutionary process and, as Deniker says, to approach “man, considered as an animal.” From this perspective, all the factors previously considered decisive indicators of race became at best secondary, while attention became focused on the hard evidence provided by skeletal remains. Many researchers found particularly compelling the “cephalic index”—the ratio of skull length to breadth—pioneered by Anders Retzius, and promoted by Morton, Nott, Gliddon, Broca, Huxley, and others. Gathered by researchers and physicians who were convinced that they were contributing to human self-understanding, the evidence from craniology was, by the end of the nineteenth century, unmanageably huge, with statistics flooding in from countless sources, many of them published in obscure journals in the various languages of Europe. By 1899, when Deniker’s work began to appear, over ten million skulls had been measured, some in over a hundred ways.

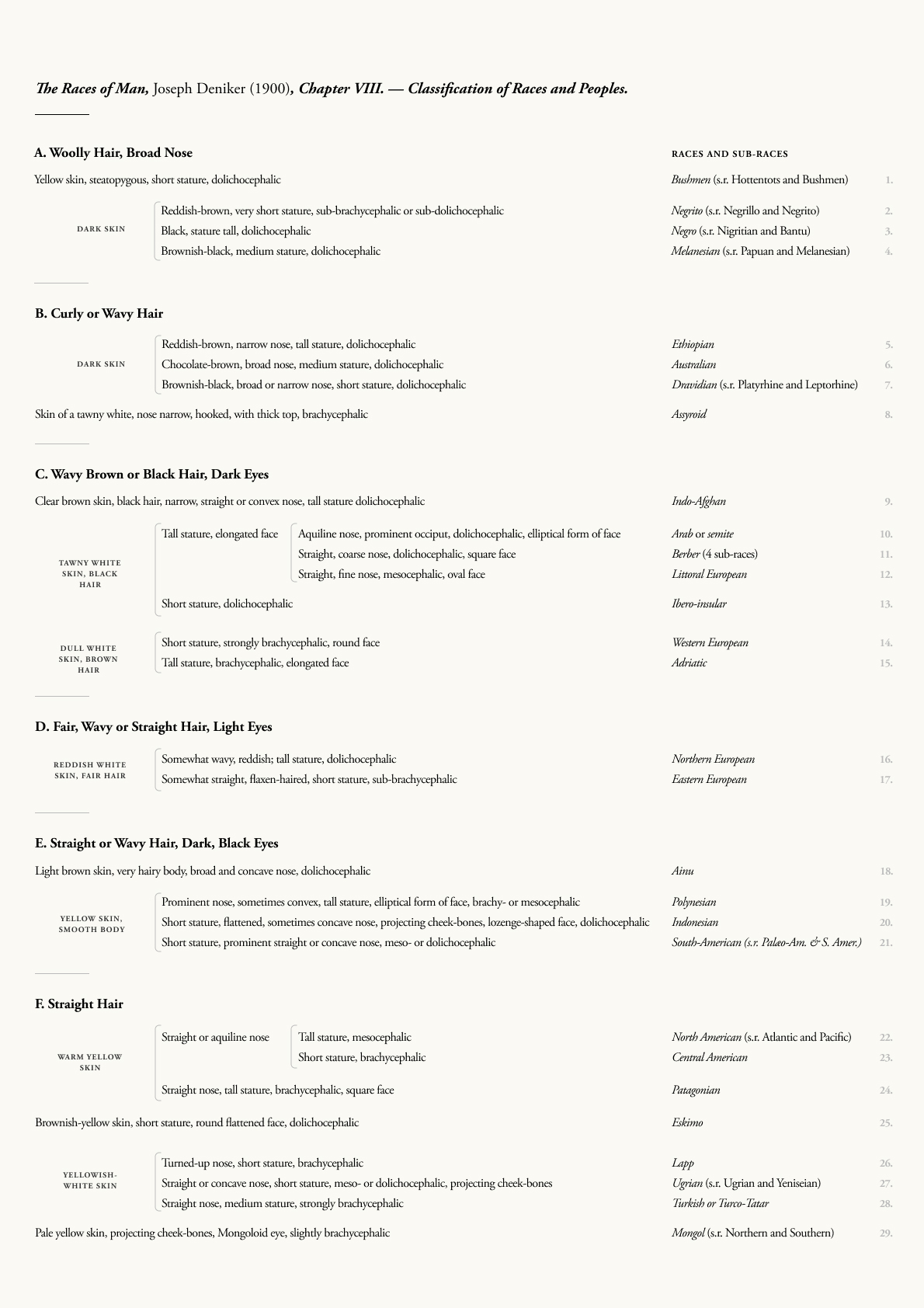

Deniker commanded this immense and disorderly field of primary and secondary data better than anyone, establishing the dolichocephalic, mesocephalic, and brachycephalic measurements and their indices for a dizzying number of categories and sub-categories, some of which Deniker introduced or to which he gave new names. In all, he identified twenty-nine races organized into seventeen groups. In Europe alone, he identified six principal races and four sub-races, spread out over four regions, determined primarily by the cephalic index.

One of the most consequential of Deniker’s terminological innovations was the “Nordic” (la race nordique) race whose ancestral homelands included northern and eastern England, south-western Ireland, Scandinavia, Frisia, and northern Germany. (See also Virchow and Haeckel). In the English translation, this became the “Northern” race, but the term Nordic was picked up by the conservationist Madison Grant, whose The Passing of the Great Race (1916) argued that the waves of immigrants from southern and eastern Europe were threatening the dominance of the Nordic race in America, and that an aggressive program of separation and quarantine should be instituted as a way of reducing the threat to the racial stock represented by the proliferation of “unfitness” or other undesirable racial traits that were, Grant said, rife among non-Nordics.

The term Nordic or Nordique may have come to Grant from Deniker, but Deniker himself never engaged in characterizations of races or race-ranking, and focused entirely on physical evidence. As the introduction to his book indicates, Deniker was himself altogether unconvinced that such terms as species, variety, type, or race had satisfactory definitions, and retained the category of race only out of deference to conventional usage; his own preference was for “ethnic group.” He gave frequent voice to his exasperation with the imprecision of the terms supposedly guiding the inquiry and with the epidemic of index-making that the inquiry had provoked. Indeed, at one point Deniker suggests that his two-dimensional grids were so complex that a third dimension would be required in order to represent the actual state of things.

Deniker had thus gathered a great many facts relevant to an investigation of “the races of man” without having settled the question of what a race—or species, or type, or variety—might be. He concluded his book with a series of appendices presenting figures for the average height of men and the cephalic index (with over three hundred groups tabulated in both categories) as well as a smaller compilation of statistics documenting the “nasal index of living subjects.”

At the time of Deniker’s publication, one of the most widely read books on race in Europe was William Z. Ripley’s The Races of Europe: A Sociological Study,* which had followed Topinard, and Broca in arguing for three races on the European continent—the Teutonic, the Alpine, and the Mediterranean—identified by their characteristic cephalic indices. Selections from Ripley’s 1899 article in response to the early publication of some of Deniker’s findings are printed below.

Ripley’s defense of his three-race partition and his criticism of Deniker, whom he saw as his chief rival, give both a sense of the kind of detail that could by this time be deployed in such arguments and of the growing uncertainty surrounding the very concept of race itself. Criticizing Deniker for studying existing populations rather than “ideal” types that would be more representative, Ripley, citing Topinard, suggests that races are best considered as abstractions; he even entertains the possibility that his own three races might be reduced by mere reflection to two or even to one: a unified human race with an Asian or African origin.

Ripley’s stout defense of the race concept despite his acceptance of the subjective nature of racial categories suggests the continuing grip of essentialist and polygenist thinking. And his recourse to the “type,” the stable essence underlying variation, suggests once again how the race concept could secrete itself in a term that did not carry an association with racism and did not depend on a belief in discrete human populations. [For types, see Hunt, Galton, Vogt, Haeckel, Quatrefages de Bréau, Topinard, and Virchow; see also George W. Stocking, Jr., and Herbert H. Odom in Further Reading.]

Deniker’s exasperation with the term “race” did not prevent his work from influencing a number of reactionary intellectuals and politicians who seized on his definition of races as distinct “somatological units” and on his identification of a “Nordic” race. In addition to Madison Grant, those impressed by Deniker’s work, as well as by Ripley’s, included Houston Stewart Chamberlain, Lothrop Stoddard, Oswald Spengler, and Adolf Hitler.

*William Z. Ripley, The Races of Europe: A Sociological Study (New York: D. Appleton, 1899). Ripley’s book was substantially rewritten by Carleton S. Coon and published in 1939. Richard McMahon’s The Races of Europe: Construction of National Identities in the Social Sciences, 1839-1939 (London: Palgrave, 2016) takes its title from Ripley.

The Races of Man

Introduction. Ethnic Groups and Zoological Species.

The innumerable groups of mankind, massed together or scattered, according to the varying nature of the earth’s surface, are far from presenting a homogeneous picture. Every country has its own variety of physical type, language, manners, and customs. Thus, in order to exhibit a systematic view of all the peoples of the earth, it is necessary to observe a certain order in the study of these varieties, and to define carefully what is meant by such and such a descriptive term, having reference either to the physical type or to the social life of men. This we shall do in the subsequent chapters as we proceed to develop this slight sketch of the chief general facts of the physical and psychical life of man, and of the most striking social phenomena of the groups of mankind.

But there are some general terms which are of more importance than others, and their meaning should be clearly understood from the first. I refer to expressions like “people,” “nation,” “tribe,” “race,” “species,” in short, all the designations of the different groupings, real or theoretic, of human beings. Having defined them, we shall by so doing define the object of our studies.

Since ethnography and anthropology began to exist as sciences, an attempt has been made to determine and establish the great groups amongst which humanity might be divided. A considerable diversity of opinion, however, exists among leading scientific men not only as to the number of these groups, of these “primordial divisions” of the human race, but, above all, as to the very nature of these groups. Their significance, most frequently, is very vaguely indicated.

In zoology, when we proceed to classify, we have to do with beings which, in spite of slight individual differences, are easily grouped around a certain number of types, with well-defined characters, called “species.” An animal can always be found which will represent the “type” of its species. In all the great zoological collections there exist these “species-types,” to which individuals may be compared in order to decide if they belong to the supposed species. We have then in zoology a real substratum for the determination of species, those primordial units which are grouped afterwards in genera, families, orders, etc.

Is it the same for man? Whilst knowing that the zoological genus Homo really exists quite distinct from the other genera of the animal kingdom, there still arises the question as to where the substratum is on which we must begin operations in order to determine the “species” of which this genus is composed. The only definite facts before us are these groups of mankind, dispersed over the whole habitable surface of the globe, to which are commonly given the names of peoples, nations, clans, tribes, etc. We have presented to us Arabs, Swiss, Australians, Bushmen, English, Siouan Indians, Negroes, etc., without knowing if each of these groups is on an equal footing from the point of view of classification.

Do these real and palpable groupings represent unions of individuals which, in spite of some slight dissimilarities, are capable of forming what zoologists call “species,” “sub-species,” “varieties,” in the case of wild animals, or “races” in the case of domestic animals? One need not be a professional anthropologist to reply negatively to this question. They are ethnic groups formed by virtue of community of language, religion, social institutions, etc., which have the power of uniting human beings of one or several species, races, or varieties, and are by no means zoological species; they may include human beings of one or of many species, races, or varieties.

Here, then, is the first distinction to make: the social groups that we are to describe in this work under the names of clans, tribes, nations, populations, and peoples, according to their numerical importance and the degree of complication of their social life, are formed for us by the union of individuals belonging usually to two, three, or a greater number of “somatological units.” These units are “theoretic types” formed of an aggregation of physical characters combined in a certain way. . . .

Without wishing to enter into a discussion of details, it seems to me that where the genus Homo is concerned, one can neither speak of the “species,” the “variety,” nor the “race” in the sense that is usually attributed to these words in zoology or in zootechnics.

In effect, in these two sciences, the terms “species” and “variety” are applied to wild animals living solely under the influence of nature; whilst the term “race” is given in a general way to the groups of domestic animals living under artificial conditions created by an alien will, that of man, for a well-defined object.

Let us see to which of these two categories man, considered as an animal, may be assimilated.

By this single fact, that even at the very bottom of the scale of civilisation man possesses articulate speech, fashions tools, and forms himself into rudimentary societies, he is emancipated from a great number of influences which Nature exerts over the wild animal; he lives, up to a certain point, in an artificial environment created by himself. On the other hand, precisely because these artificial conditions of life are not imposed upon him by a will existing outside himself, because his evolution is not directed by a “breeder” or a “domesticator,” man cannot be compared with domestic animals as regards the modifications of his corporeal structure.

The data relating to the formation of varieties, species, and races can therefore be applied to the morphological study of man only with certain reservations.

This being established, let us bear in mind that even the distinction between the species, the variety (geographical or otherwise), and the race is anything but clearly marked. Besides, this is a question that belongs to the domain of general biology, and it is no more settled in botany or in zoology than in anthropology. . . .

The idea of “species” must rest on the knowledge of two orders of facts, the morphological resemblances of beings and the lineal transmission of their distinctive characters. Here, in fact, the formula of Cuvier is still in force to-day in science. “The species is the union of individuals descending one from the other or from common parents, and of those who resemble them as much as they resemble each other.” (I have italicised the passage relating to descent.) It is necessary then that beings, in order to form a species, should be like each other, but it is obvious that this resemblance cannot be absolute, for there are not two plants or two animals in nature which do not differ from each other by some detail of structure; the likeness or unlikeness is then purely relative; it is bound to vary within certain limits. . . .

In the case of man, as in that of the majority of plants and animals, fertility or non-fertility among the different groups has not been experimentally proved, to enable us to decide if they should be called “races” or “species.” To a dozen facts in favour of one of the solutions, and to general theories in regard to half-breeds, can be opposed an equal number of facts, and the idea, not less general, of reversion to the primitive type. And again, almost all the facts in question are borrowed from cross-breeding between the Whites and other races. No one has ever tried cross-breeding between the Australians and the Lapps, or between the Bushmen and the Patagonians, for example. If certain races are indefinitely fertile among themselves (which has not yet been clearly shown), it may be there are others which are not so. A criterion of descent being unobtainable, the question of the rank to be assigned to the genus Homo is confined to a morphological criterion, to the differences in physical type.

According to some, these differences are sufficiently pronounced for each group to form a “species”; according to others they are of such a nature as only to form racial distinctions. Thus it is left to the personal taste of each investigator what name be given to these.

We cannot do better than cite upon this point the opinion of a writer of admitted authority. “It is almost a matter of indifference,” says Darwin, “whether the so-called races of man are thus designated, or ranked as ‘species’ or ‘sub-species,’ but the latter term appears the most appropriate.” The word “race” having been almost universally adopted nowadays to designate the different physical types of mankind, I shall retain it in preference to that of “sub-species,” while reiterating that there is no essential difference between these two words and the word “species.”

From what has just been said, the question whether humanity forms a single species divided into varieties or races, or whether it forms several species, loses much of its importance.

The whole of this ancient controversy between monogenists and polygenists seems to be somewhat scholastic, and completely sterile and futile; the same few and badly established facts are always reappearing, interpreted in such and such a fashion by each disputant according to the necessities of his thesis, sometimes led by considerations which are extra-scientific. Perhaps in the more or less near future, when we shall have a better knowledge of present and extinct races of man, as well as of living and of fossil animal species most nearly related to man, we shall be able to discuss the question of origin. At the present time we are confined to hypothesis without a single positive fact for the solution of the problem. We have merely to note how widely the opinions of the learned differ in regard to the origin of race of certain domestic animals, such as the dog, the ox, or the horse, to get at once an idea of the difficulty of the problem. And yet, in these cases, we are dealing with questions much less complicated and much more carefully studied.

Moreover, whether we admit variety, unity or plurality of species in the genus Homo we shall always be obliged to recognise the positive fact of the existence in mankind of several somatological units having each a character of its own, the combinations and the intermingling of which constitute the different ethnic groups. Thus the monogenists, even the most intractable, as soon as they have established hypothetically a single species of man, or of his “precursor,” quickly cause the species to evolve, under the influence of environment, into three or four or a greater number of primitive “stocks,” or “types,” or “races,”—in a word, into somatological units which, intermingling, form “peoples,” and so forth.

We can sum up what has just been said in a few propositions. On examining attentively the different “ethnic groups” commonly called “peoples,” “nations,” “tribes,” etc., we ascertain that they are distinguished from each other especially by their language, their mode of life, and their manners; and we ascertain besides that the same traits of physical type are met with in two, three, or several groups, sometimes considerably removed the one from the other in point of habitat. On the other hand, we almost always see in these groups some variations of type so striking that we are led to admit the hypothesis of the formation of such groups by the blending of several distinct somatological units.

It is to these units that we give the name “races,” using the word in a very broad sense, different from that given to it in zoology and zootechnics. It is a sum-total of somatological characteristics once met with in a real union of individuals, now scattered in fragments of varying proportions among several “ethnic groups,” from which it can no longer be differentiated except by a process of delicate analysis. . . .

Certain authors make a distinction between ethnography and ethnology, saying the first aims at describing peoples or the different stages of civilisation, while the second should explain these stages and formulate the general laws which have governed the beginning and the evolution of such stages. Others make a like distinction in anthropology, dividing it theoretically into “special” and “general,” the one describing races, and the other dealing with the descent of these races and of mankind as a whole. But these divisions are purely arbitrary, and in practice it is impossible to touch on one without having given at least a summary of the other. The two points of view, descriptive and speculative, cannot be treated separately. A science cannot remain content with a pure and simple description of unconnected facts, phenomena, and objects. It requires at least a classification, explanations, and, afterwards, the deduction of general laws. In the same way, it would be puerile to build up speculative systems without laying a solid foundation drawn from the study of facts. Already the distinction between the somatic and the ethnic sciences is embarrassing; thus psychological and linguistic phenomena refer as much to the individual as to societies. They might, strictly speaking, be the subject of a special group of sciences. In the same way, the facts drawn from the somatic and ethnic studies of extinct races are the subject of a separate science—Palethnography, otherwise Prehistory, or Prehistoric Archæology. (1-10)

EXCEPTION has frequently been taken to the anthropological classifications of different authors, from the time of F. Bernier (1672) to our own days, in that they recognise in humanity an excessively variable number of races, from two (Virey in 1775) up to thirty-four (Haeckel in 1879). These strictures are by no means deserved, seeing that those who make them almost always compare classifications dating from various times, and consequently drawn up from facts and documents which are not comparable. In all sciences, classifications change in proportion as the facts or objects to be classed become better known.

Besides, if we go to the root of the matter we perceive that the diversity in the classifications of the genus Homo is often only apparent, for most classifications confuse ethnic groups and races. If my readers refer back to what I said in the introduction on “races” and “ethnic groups,” they will understand all the difficulties this causes.

In order to class peoples, nations, tribes, in a word, “ethnic groups,” we ought to take into consideration linguistic differences, ethnic characters, and especially, in my opinion, geographical distribution. It is thus that I shall describe the different peoples in the subsequent chapters, while classing them geographically. But for a classification of “races” (using the word in the sense given to it in the introduction), it is only necessary to take into account physical characters. We must try to determine by the anthropological analysis of each of the ethnic groups the races which constitute it; then compare these races one with another, unite those which possess most similarities in common, and separate those which exhibit most dissimilarities.

On making these methodic groupings we arrive at a small number of races, combinations of which, in various proportions, are met with in the multitude of ethnic groups.

Let us take for example the Negrito race, of which the Aetas of the Philippines, the Andamanese, and the black Sakai are the almost pure representatives. This race is found again here and there among the Melanesians, the Malays, the Dravidians, etc. In all these populations the type of the Negrito race is revealed on one side by the presence of a certain number of individuals who manifest it almost in its primitive purity, and on the other by the existence of a great number of individuals, whose traits likewise reproduce this type, but in a modified form, half hidden by characters borrowed from other races. Characteristics of various origin may thus be amalgamated, or merely exist in juxtaposition.

Race-characters appear with a remarkable persistency, in spite of all intermixtures, all modifications due to civilisation, change of language, etc. What varies is the proportion in which such and such a race enters into the constitution of the ethnic group. A race may form the preponderating portion in a given ethnic group, or it may form a half, a quarter, or a very trifling fraction of it; the remaining portion consisting of others. Rarely is an ethnic group composed almost exclusively of a single race; in this case the notion of race is confused with that of people. We may say, for example, that the tribes called Bushmen, Aetas, Mincopies, Australians, are formed of a race still almost pure; but these cases are rare. Already it is difficult to admit that there is but one race, for example, among the Mongols; and if we pass to the Negroes we find among them at least three races which, while being connected one with another by a certain number of common characteristics, present, nevertheless, appreciable differences. Now, each of these races may be combined, in an ethnic group, not only with a kindred race, but also with other races, and it is easy to imagine how very numerous may be these combinations.

I have just said that the number of human races is not very considerable; however, reviewing the different classifications proposed, in chronological order, it will be seen that this number increases as the physical characters of the populations of the earth become better known. Confining ourselves to the most recent and purely somatological classifications, we find the increase to be as follows:—In 1860, Isid. Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire admitted four principal races or “types,” and thirteen secondary ones. In 1870, Huxley proposed five principal races or types, and fourteen secondary ones or “modifications.” Finally, in 1878, Topinard enumerated sixteen races, and increased this number in 1885 to nineteen. In mixed classifications, based on both somatic and ethnic characters, a very much greater number of sub-divisions is found, but the reason of that is that “ethnic groups” are included.

Putting these aside, we see in the most complete mixed classifications only four or five principal races, and twelve to eighteen secondary races. Thus Haeckel and Fr. Mueller admit four principal races (called “tribes” by Haeckel, “sub-divisions” by Mueller), and twelve secondary races (called “species” and sub-divided into thirty-four “races” by Haeckel, called “races” and sub-divided into numerous “peoples” by Fr. Mueller). On the other hand, De Quatrefages sub-divides his five “trunks” into eighteen “branches,” each containing several ethnic groups, which he distinguishes under the names of “minor branches” and “families.”

Some years ago I proposed a classification of the human races, based solely on physical characters. Taking into account all the new data of anthropological science, I endeavoured, as do the botanists, to form natural groups by combining the different characters (colour of the skin, nature of the hair, stature, form of the head, of the nose, etc.), and I thus managed to separate mankind into thirteen races. Continuing the analysis further, I was able to give a detailed description of the thirty sub-divisions of these races, which I called types, and which it would have been better to call secondary races, or briefly “races.” A mass of new material, and my own researches, have compelled me since then to modify this classification. This is how it may be summarised in the form of a table, giving to my former “types” the title of race or sub-races, and grouping them under six heads—

My table contains the enumeration of the principal somatic characters for each race. Arranged dichotomically for convenience of research, it does not represent the exact grouping of the races according to their true affinities. It would be vain to attempt to exhibit these affinities in the lineal arrangement of a table; each race, in fact, manifests some points of resemblance, not only with its neighbours in the upper or lower part of the table, but also with others which are remote from it, in view of the technical necessities of construction of such a table. In order to exhibit the affinities in question, it would be necessary to arrange the groups according to the three dimensions of space, or at least on a surface where we can avail ourselves of two dimensions. In the ensuing table are included twenty-nine races, combined into seventeen groups, arranged in such a way that races having greatest affinities one with another are brought near together. Seven of these groups only are composed of more than one race. They may be called as follows (see the table):—XIII., American group; XII., Oceanian; II., Negroid; VIII., North African; XVI., Eurasian; X., Melanochroid; IX., Xanthochroid. This table shows us clearly that the Bushman race, for example, has affinities with the Negritoes (short stature) and the Negroes (nature of the hair, form of nose); that the Dravidian race is connected both with the Indonesian and the Australian; that the place of the Turkish race is, by its natural affinities, between the Ugrians and the Mongols; that the Eskimo have Mongoloid and American features; that the Assyroids are closely related to the Adriatics and the Indo-Afghans; that the latter, by the dark colour of their skin, recall the Ethiopians, and the Arabs by the shape of the face, etc. (280-87)

The Races of Man

“Deniker’s Classifications of the Races of Europe”

A most notable work upon the physical characteristics of the races of Europe by Dr. J. Deniker, Librarian of the Musée d’Histoire Naturelle, at Paris, is about to appear in the forthcoming Compte Rendu de l’Association française pour l’Avancement des Sciences; and in even more extended form in the Mémoires de la Société d’Anthropologie at Paris. . . .

Let us at the outset state most positively that, so far as one can judge from the preliminary sketches, the work promises to be of the very highest scientific importance; it betrays a zeal in the examination of original sources, as well as a careful discrimination in their correction and digestion, which cannot be too highly commended. The author seems to have exhausted almost every possible source of information as to the cephalic index, the colour of the hair and eyes and the stature of the European peoples in all the known languages. . . .

Deniker’s raw materials—his data as to cephalic index, colour of hair and eyes and stature—differ only in slight detail from our own; albeit, they were apparently collected in entire independence of one another. That is a comforting circumstance, which strikingly serves to confirm the fundamental accuracy of each. Only in one or two details do we take exception to his data. Thus in Holland, the extremely brachycephalous spot at the mouth of the Scheldt, does not seem to be sufficiently emphasized by him. In Denmark, where we all are obliged to confess lamentable paucity of observations, there is also a discrepancy with our own figures as to the head form. . . .

Here are the data on which all authorities are now perfectly agreed. I give them in his words: “the cephalic index is grouped in four regions: one dolichocephalic with an encircling zone of mesocephaly in the north (Scandinavia); a more strongly dolichocephalic one in the south (Mediterranean); a very broad-headed one in West Central Europe (Alps); and finally a sub-brachycephalic one in the east centre.” (Russia, etc.). . . .

Now we reach our apparent dilemma. From almost entire agreement as to the distribution of the three principal physical characteristics each by itself, Deniker reaches widely different conclusions as to their combination into racial types, from nearly every standard authority in Europe. . . Deniker differs from all others in combining his three separate physical traits into six principal races and four or more sub-races, to which entirely new names, unknown to anthropologists heretofore, are assigned. This seemingly unnecessary rejection of time-honoured names adds greatly to the difficulty of comparing his conclusions with those of others. . . .

The fact that from the same data such widely variant racial conclusions may be drawn is, at first sight, calculated to shake one’s confidence in the whole attempt at a systematic somatological classification of the population of Europe. This we believe to be an unjustifiable inference. Deniker is too well equipped an anthropologist to go astray in such matters . . . . What, then, is the matter? . . .

The controversy involves, it seems to us, a question which has been much discussed of late by naturalists concerning the definition of the word “type.” For in anthropology the term “race”—alas! so often lightly used—corresponds in many respects to the word “type” in zoology.

Deniker’s elaborate scheme of six main, and four secondary, races, is, in reality, not a classification of “races” at all, in the sense in which Topinard and others have so clearly defined it. It is rather a classification of existing varieties. Here is Topinard’s definition of the word “race”: It is “in the present state of things an abstract conception, a notion of continuity in discontinuity, of unity in diversity. It is the rehabilitation of a real but directly unattainable thing.” Apply this criterion to Deniker’s six “races” and four “sub-races.” Is there any ideality about them? Is there any “unity” in his scheme? . . .

The primary reason why, we affirm, Deniker has not carried his analysis far enough really to have discovered “races” lies in his neglect to eliminate all the modifying influences of environment, physical or social; of selection in its various phases; and of those other disturbing factors; which, together with the direct and perhaps predominant influences of heredity, constitute the figure of man as he stands. Wherever Deniker has spied a more or less stable combination of traits, he has hit upon it as a race, to paraphrase a well-known injunction. . . .

Only one great, insurmountable obstacle stands in the way of the ardent evolutionist who would finally run even the three primary types to earth in the far distant past. How shall we ever reconcile the polar difference in every respect between the broad-headed Asiatic type of central Europe and its two dolichocephalic neighbours on the north and south. Suppose, as we have done, that even these last two finally are traceable to a common African source, are we to confess the existence of two distinct and primary forms of the genus Homo—one Asiatic and one African? are we to deny, in other words, the fundamental unity of the human species? We are entering upon the field of speculation pure and simple.

C. Loring Brace, “‘Physical’ Anthropology at the Turn of the Last Century,” in Michael A. Little and Kenneth A. R. Kennedy, eds., Histories of American Anthropology in the Twentieth Century (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2010), 25-54.

Nancy Stepan, “Race after Darwin: The World of the Physical Anthropologists,” in The Idea of Race in Science: Great Britain, 1800-1960 (Houndsmills: Macmillan Press, 1982), 83-110.

Herbert H. Odom, “Generalizations on Race in Nineteenth-Century Physical Anthropology,” Isis 58 (Spring, 1967) 1: 4-18.

George W. Stocking, Jr., “The Persistence of Polygenist Thought in Post-Darwinian Anthropology,” in Race, Culture, and Evolution: Essays in the History of Anthropology (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1982), 42-68.